Comprehensive Guide to End Milling: Process, Applications, and Optimization

Abstract: This article provides a detailed professional guide on end milling. It covers its core definition, process details, tool selection, parameter optimization, industry applications, and provides an in-depth analysis of its advantages, challenges, and cost-effectiveness. It aims to serve as a practical reference for manufacturing engineers, technicians, and decision-makers.

1. What is End Milling?

End milling is a fundamental milling process characterized by the use of a multi-toothed cutter called an end mill, which utilizes its cutting edges on both its end face and periphery to machine a workpiece. Unlike peripheral milling, which primarily relies on the tool's side edges for cutting, end milling focuses more on using the tool's end teeth to remove material. It is exceptionally well-suited for creating flat surfaces, pockets, steps, and complex three-dimensional contours. This versatility makes it a critical step in the entire manufacturing process, from roughing to finishing, and is the primary method on CNC machining centers for transforming a raw material blank into a finished part geometry.

2. Why is End Milling So Important?

End milling holds a pivotal position in manufacturing, its importance stemming from its unparalleled versatility and efficiency. It can perform multiple machining tasks in a single setup—such as face milling, pocketing, and contour profiling—significantly reducing workpiece handling times and overall processing time, thereby enhancing production efficiency and precision. For the complex components common in modern industry, end milling is the core technology for achieving high precision and superior surface quality requirements. From rapid prototyping to large-scale mass production, end milling is a key manufacturing process supporting product realization.

3. What is the History of End Milling?

The development of end milling technology is closely linked to the evolution of machining history. Early milling operations primarily used simple cylindrical cutters. With the surge in demand for standardized parts during the 19th-century Industrial Revolution, milling machines and cutter technology began to develop rapidly. The concept of the end mill took shape and became standardized in the early 20th century. Around World War II, the introduction of carbide materials significantly improved tool durability and cutting speeds. The real revolution came with the advent of Numerical Control (NC) technology, which made the complex path control of end milling possible and eventually evolved into today's Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machining, achieving unprecedented levels of automation, precision, and efficiency.

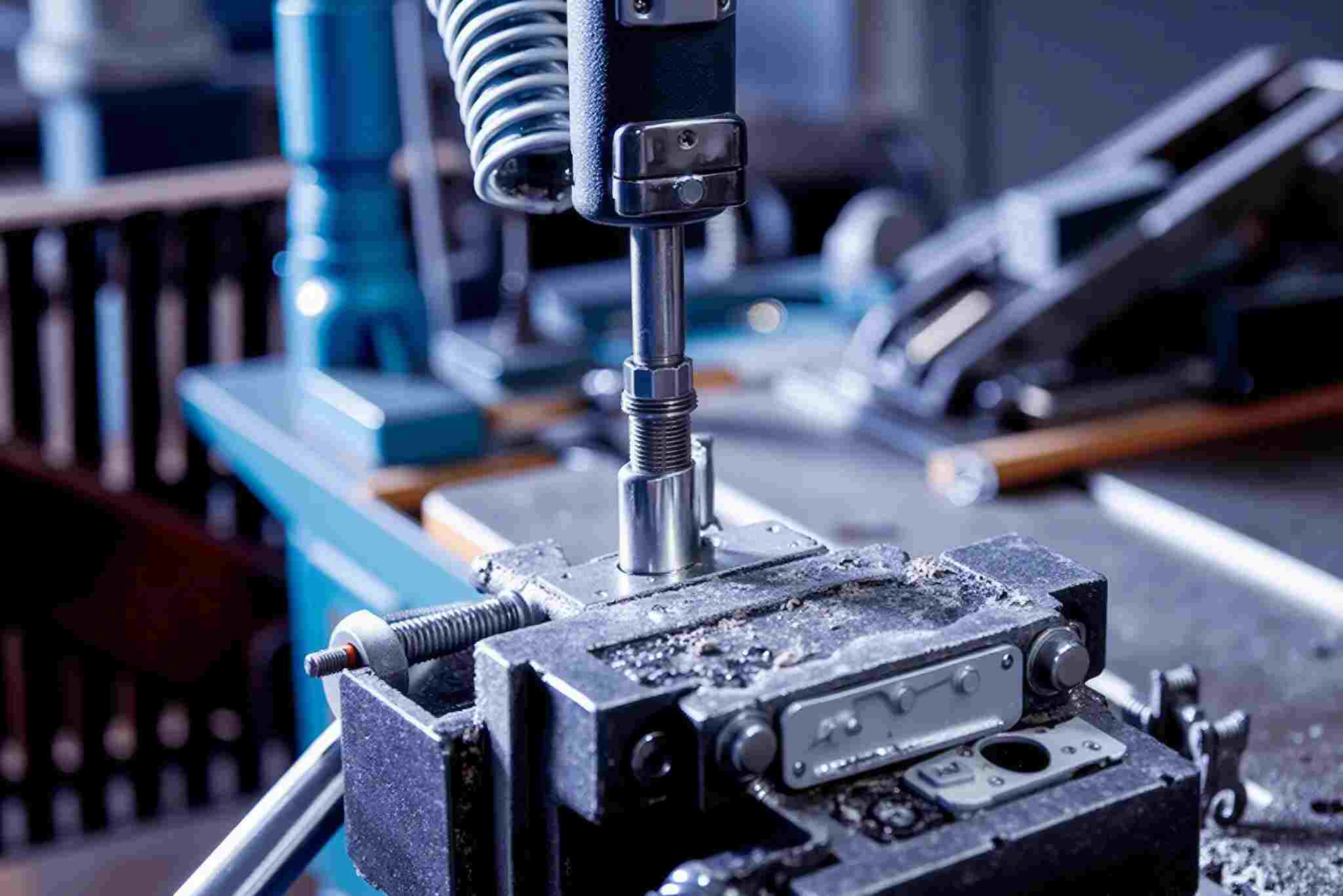

4. How is the End Milling Process Conducted?

A typical end milling process follows a series of meticulous steps. First, the workpiece must be securely clamped to the machine table, usually using a vise, clamps, or a dedicated fixture to ensure stability. Next, a suitable end mill is selected and precisely installed into the machine spindle's toolholder, such as an ER collet or shrink-fit holder. The operator or programmer then inputs or generates the machining program (G-code) into the CNC system and sets the workpiece coordinate system origin using a tool setter. Once machining starts, the spindle rotates the end mill at high speed while the tool moves along a pre-defined three-dimensional path, its end and side teeth progressively removing material. Throughout the process, the coolant system operates continuously to cool the tool and workpiece, lubricate the cutting zone, and effectively flush away chips, ensuring smooth operation and surface quality.

5. What are the Types of End Mills?

The variety of end mills is extensive, categorized into numerous types based on different machining needs. By tool material, there are cost-effective but heat-sensitive High-Speed Steel (HSS) end mills; carbide end mills, the workhorse of modern machining, offering a balance of hardness and toughness; and ceramics and CBN/PCD tools for high-speed machining or difficult-to-machine materials. Structurally, they can be solid, brazed, or indexable insert types, with indexable types being popular for face milling and high-volume roughing due to their economy. Geometrically, they are distinguished by the number of flutes (2-flute for good chip evacuation in aluminum, 3-flute for general purpose, 4 or more flutes for high stability in steel), straight or various helix angles, and specialized types like ball nose end mills (for 3D surfaces) and corner radius end mills (with rounded corners for stronger tips).

6. Which Workpiece Materials are Suitable for End Milling?

End milling has an extremely wide range of material applicability, covering almost all common engineering materials. In the realm of metals, it can efficiently process everything from softer aluminum, copper, and their alloys, to various carbon steels, alloy steels, tool steels, and even highly challenging materials like stainless steel, titanium alloys, and nickel-based superalloys. Furthermore, most engineering plastics (e.g., ABS, Nylon, PEEK), composite materials like Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer (CFRP), and wood can be precisely shaped via end milling. The key lies in selecting the appropriate end mill material, geometry, and cutting parameters based on the specific material properties.

7. What Machines and Tools are Required for End Milling?

The core equipment for performing end milling is the milling machine, with CNC Vertical Machining Centers (VMCs) and Horizontal Machining Centers (HMCs) being the mainstream, offering high levels of automation and precision. For simpler tasks, manual milling machines can also be used. Beyond the main machine, the required tooling system includes: various types of end mills; toolholder systems for holding the tools, such as collet chucks, shrink-fit holders, and hydraulic holders; fixtures for securing the workpiece, like precision vises, chucks, or dedicated jigs; and auxiliary equipment like tool setters, coolant supply systems, and chip removal units.

8. What are the Important Parameters in End Milling?

Successful end milling relies on a precise understanding and control of several key cutting parameters. Cutting Speed (Vc) is the linear speed at the cutting edge relative to the workpiece surface, typically measured in meters per minute (m/min), directly affecting tool life and machining efficiency. Spindle Speed (S) is the rotational speed of the machine spindle, calculated from the cutting speed and tool diameter. Feed per Tooth (fz) is the distance the workpiece (or tool) moves in the feed direction for each cutting edge of the tool, influencing chip formation, cutting forces, and surface finish. Feed Rate (F) is the total distance the tool travels per minute. Axial Depth of Cut (ap) and Radial Depth of Cut (ae) define the amount of material the tool engages in the axial and radial directions, respectively, collectively determining the Material Removal Rate (MRR).

9. What Advanced Technologies and Toolpath Strategies Can Improve End Milling Efficiency?

To maximize end milling efficiency, a range of advanced technologies and toolpath strategies have been developed. High-Speed Machining (HSM) employs a combination of small depths of cut, high feed rates, and high spindle speeds to reduce cutting forces, minimize distortion, and improve surface finish. Trochoidal Milling strategies cause the tool to follow a trochoidal path when engaging the material, avoiding full-width cuts and greatly improving heat dissipation and chip evacuation, particularly suitable for efficient roughing of deep pockets and difficult-to-machine materials. Dynamic Milling (or Adaptive Clearing) maintains a constant, small radial depth of cut and a full axial depth of cut, combined with a continuous toolpath, achieving high material removal rates while protecting the tool. Optimized toolpaths generated by modern CAM software, such as smooth cornering, ramp milling, and helical interpolation, can significantly reduce machine vibration and non-cutting time, thereby improving overall efficiency.

10. In Which Industries is End Milling Applied?

As a fundamental manufacturing process, end milling finds applications across virtually all modern industrial sectors. In the aerospace industry, it is used to machine complex, high-strength components like airframe structures, engine casings, and turbine blades. The automotive manufacturing industry utilizes it to produce engine blocks, transmission cases, molds, and various precision components. The mold and die industry itself is a major user of end milling, relying on high-precision end milling to create cavities for injection molds, die-casting molds, and stamping dies. In the medical device field, it is responsible for manufacturing bone screws, joint implants, and precision surgical instruments. Additionally, enclosures and heat sinks in the electronics industry, and pump bodies, valve bodies, etc., in general machinery all depend on end milling technology.

11. What are the Advantages and Disadvantages of End Milling?

The main advantage of end milling lies in its exceptional versatility, enabling the machining of multiple geometric features with a single tool, thereby reducing tool change times and process steps. It typically offers high material removal rates and production efficiency. Under suitable conditions, it can achieve micron-level accuracy and excellent surface finish, and is highly suitable for automated and digital production. However, it also has disadvantages: the initial investment cost for CNC machines and high-quality tools is relatively high; it demands considerable skill and experience from operators and programmers; tools are consumables, incurring ongoing wear and replacement costs; and when machining deep pockets or thin-walled parts, challenges such as chip evacuation, chatter, and workpiece deformation may arise.

12. What Challenges are Encountered in End Milling and How to Overcome Them?

Common challenges in end milling include rapid tool wear or unexpected chipping, which can be mitigated by selecting wear-resistant coated tools, optimizing coolant parameters, and ensuring efficient chip evacuation. Vibration and chatter during machining severely affect surface quality and tool life; countermeasures include improving the rigidity of the process system (e.g., using high-performance toolholders, selecting variable-pitch end mills) and adjusting the combination of speed and depth of cut. Poor chip evacuation can lead to tool damage and workpiece scoring; using tools with high-pressure through-coolant, selecting end mills with large flute volumes, and employing appropriate toolpaths help resolve this issue. For thin-walled parts with low rigidity prone to deformation, it is necessary to optimize clamping forces, adopt step-by-step machining to relieve stress, and use high-speed machining strategies to minimize cutting forces.

13. What are the Key Safety Precautions in End Milling?

Safety is the top priority in end milling operations. Operators must always wear safety glasses compliant with standards to protect against flying chips and coolant. Before starting the machine, always double-check that both the workpiece and the tool are firmly clamped; any looseness can cause serious accidents. It is strictly forbidden to touch the cutting area or attempt to remove chips by hand or with any object while the spindle is rotating. When measuring, inspecting, or adjusting the workpiece, ensure the spindle has come to a complete stop. All operators should be familiar with the location and operation of the machine's emergency stop button and ensure the work area is tidy and well-lit.

14. Which Factors Affect Surface Finish and Tolerance in End Milling?

The factors affecting surface finish and dimensional tolerance in end milling are multifaceted. The condition of the tool itself is crucial, including tool runout, the sharpness of the cutting edges (wear state), and the tool's geometric design. The setting of cutting parameters, such as a feed rate that is too high leading to increased cusp height, or inappropriate spindle speeds potentially causing vibration, plays a key role. The dynamic performance of the machine tool, like spindle runout, guideway accuracy, and the servo response of the feed system, directly determines the machining outcome. Insufficient rigidity of the workpiece setup can lead to tool deflection and vibration under cutting forces. Furthermore, the choice of toolpath strategy, for instance, using climb milling generally yields better surface finish than conventional milling because it avoids the cutting edge rubbing on the machined surface.

15. What are the Key Considerations and Best Practices for End Milling?

When planning an end milling process, one must comprehensively consider the workpiece material, target geometry, quality requirements, production volume, and available equipment. In terms of best practices, climb milling should be prioritized where possible, as it allows the cutting edge to engage the material from the outside, resulting in a more stable cutting process and longer tool life. Always keep tools clean and sharp, regularly check for wear, and replace or regrind them promptly. Select the shortest and most rigid end mill possible that meets the machining requirements and use the most rigid holding method to maximize process system stability. Ensure cutting fluid accurately reaches the tool-workpiece interface; high-pressure through-coolant is crucial for difficult-to-machine materials. Finally, fully utilize the simulation capabilities of CAM software to verify programs before actual machining, avoiding collisions and gouging.

16. Is End Milling Expensive?

The cost of end milling cannot be generalized and depends on the specific application. For one-off or small-batch production, the unit cost is relatively high because the time costs for programming, setup, and first-article inspection are amortized over fewer parts. However, in mass production, these upfront costs are spread out, and its advantages of automated high efficiency come into full play, significantly reducing the unit cost. The main cost components include machine depreciation, tool consumption, labor, energy, and material costs. Through scientific tool management, parameter optimization, and efficient programming strategies, machining costs can be effectively controlled within a reasonable range.

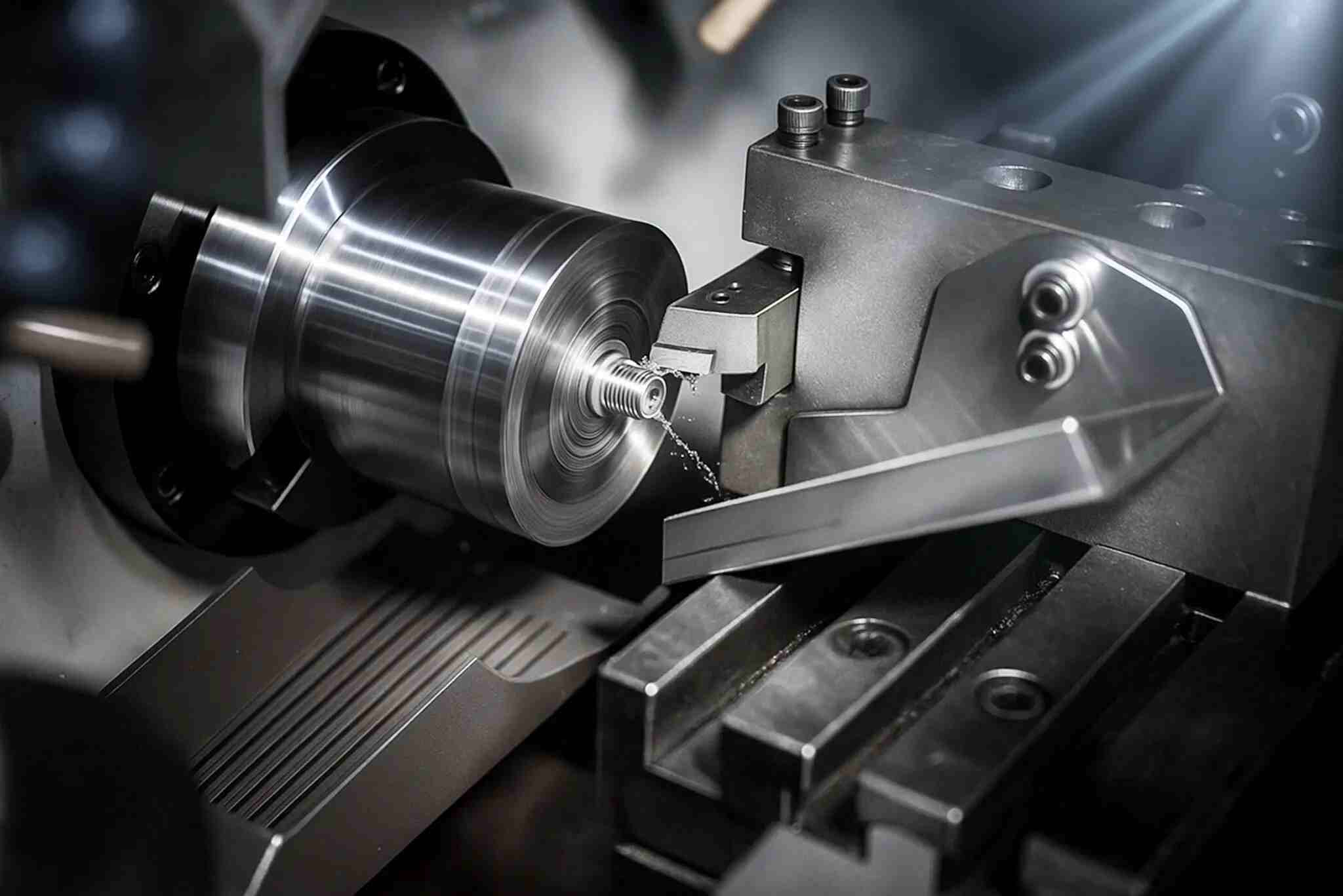

17. How Does End Milling Differ from Other Milling Methods?

End milling is most often compared to peripheral milling. Peripheral milling primarily uses the peripheral side edges of the end mill for cutting, with the main cutting force being radial; it is suitable for finishing side walls and profile milling. End milling, in contrast, mainly uses the tool's end teeth for cutting, with the main cutting force being axial, making it more adept at face milling and machining the bottoms of pockets. In practical applications, a single pass with an end mill often combines both end and peripheral milling. Compared to other specialized milling methods like face milling (which uses large face mills for highly efficient large surface machining), end milling offers greater flexibility, though it may be less efficient for purely large, flat surfaces.

18. How to Maintain and Care for End Mills?

Proper maintenance can significantly extend the service life of end mills and ensure machining stability. After each use, immediately and thoroughly remove chips and oil residue adhering to the tool and toolholder using a dedicated cleaning fluid to prevent corrosion and loss of precision. Regularly inspect the cutting edges under a magnifier or tool microscope, paying attention to signs of flank wear, chipping, etc., for timely action. Tools should be stored in a dry, vibration-free dedicated tool cabinet, avoiding collisions between cutting edges that could cause damage. When wear reaches a predetermined standard (e.g., VB value), the tool should be sent to a professional tool regrinding service for resharpening, rather than continuing to use it, as this can exacerbate tool damage and affect machining quality.

19. Conclusion

In summary, end milling is a core manufacturing technology with considerable depth and breadth, whose capabilities continue to expand alongside advancements in materials science, tool technology, and digitalization. Mastering its process principles, tool characteristics, parameter interplay, and advanced strategies is essential for any manufacturing enterprise seeking to enhance competitiveness and achieve high-quality, efficient production. Whether addressing current production challenges or embracing future smart manufacturing, end milling will continue to play an indispensable role.