A Comprehensive Analysis of Three-Axis Machining: Core Technologies, Applications, and Choices from an Engineer's Perspective

In the era of digital manufacturing, CNC machining is the cornerstone of modern industry. Among numerous machining methods, three-axis machining, with its maturity, stability, and high cost-effectiveness, occupies an absolutely mainstream position. Whether you are a novice engineer or a seasoned manufacturing expert, a thorough understanding of three-axis machining is indispensable. This article will analyze the core essence of three-axis machining from an engineer's perspective.

What is Three-Axis Machining?

From a kinematic perspective, three-axis machining refers to the coordinated movement of the CNC machine tool's cutting tool or spindle in three linear degrees of freedom. These three axes are typically defined as:

X-axis: Horizontal movement of the worktable in the left-right direction.

Y-axis: Horizontal movement of the worktable in the front-back direction.

Z-axis: Vertical movement of the spindle head in the up-down direction.

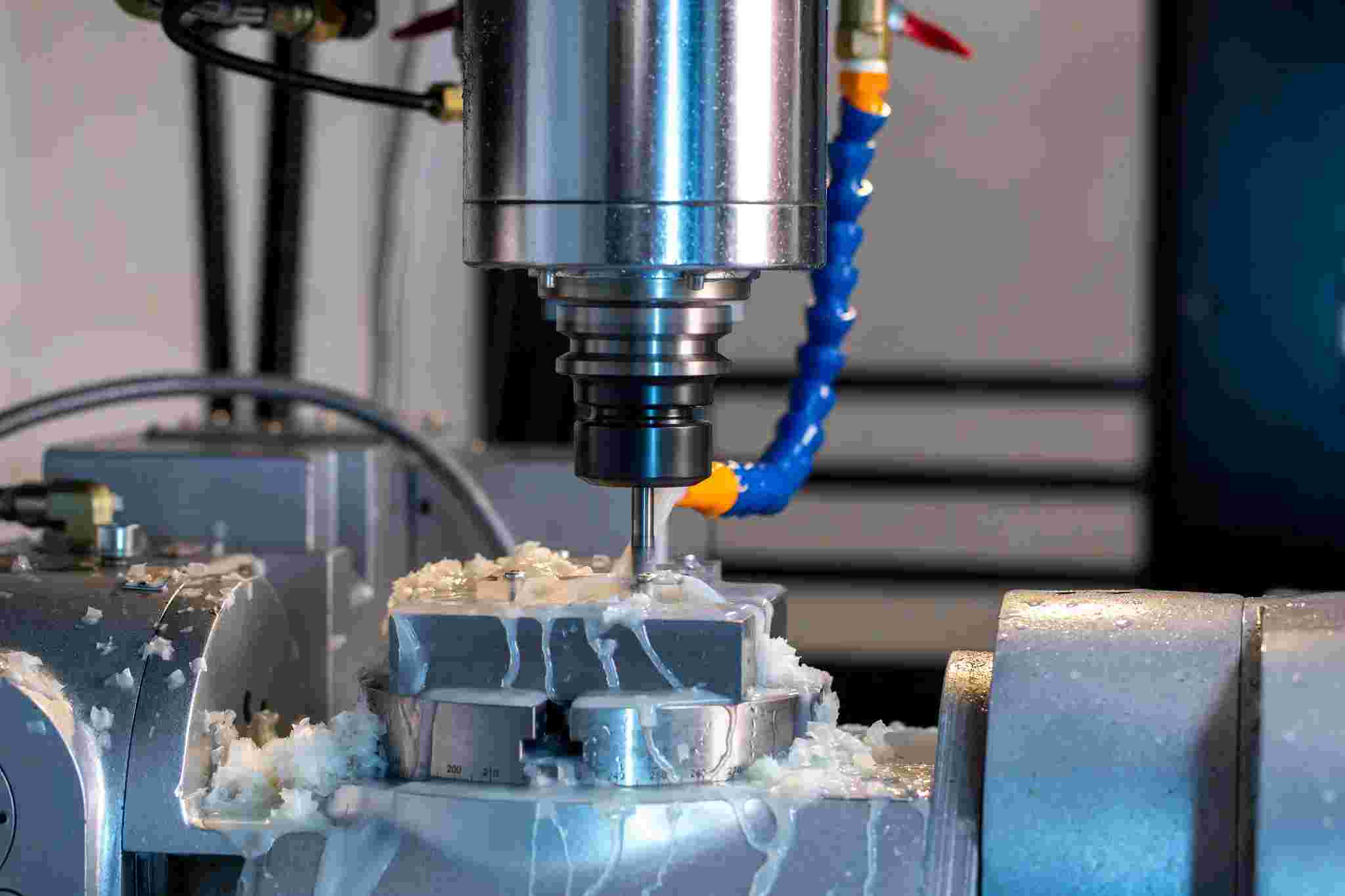

Through interpolation calculations on these three axes by the CNC control system, the cutting tool can reach any coordinate point in three-dimensional space, thereby performing cutting operations such as milling, drilling, and tapping on the workpiece fixed on the worktable. Its core characteristic is that only one face (usually the top face) of the workpiece can be machined in a single setup.

What is Three-Axis Machining?

Three-axis machining process planning is the soul of manufacturing efficiency and quality. A standard process flow is as follows:

CAD Modeling: Create a digital model of the part using 3D design software (such as SolidWorks, CATIA, UG/NX).

CAM Programming: Generate toolpaths based on the model using CAM software (such as Mastercam, Fusion 360). Engineers need to make key decisions at this stage, including:

Tool Selection: Select appropriate milling cutters, drills, etc., based on the material and application scenario (roughing, finishing).

Cutting Parameter Setting: Accurately calculate spindle speed, feed rate, depth of cut, and stepover, which directly affect tool life and surface finish.

Machining Strategy: Employ strategies such as cavity milling, face milling, and contour milling to efficiently remove material.

Workpiece Clamping: Securely fix the workpiece to the machine tool table using vises, clamping plates, or special fixtures. The rigidity and precision of the clamping are the primary prerequisites for ensuring machining accuracy.

Tool setting and configuration: Set the origin of the workpiece coordinate system, aligning the programmed virtual world with the physical world of the machine tool.

Machining execution: The machine tool automatically runs the program, completing all operations from roughing to finishing.

Quality inspection: Use calipers, micrometers, and coordinate measuring machines to inspect the dimensions and tolerances of the finished product.

Classification of Machines Used in Three-Axis Machining

Three-axis machining centers are the core equipment for performing three-axis machining. They are mainly divided into two categories:

Vertical machining centers: The spindle axis is perpendicular to the worktable. This is the most common type, with a compact structure, good rigidity, and easy clamping and observation. It is particularly suitable for machining plates, discs, molds, and small parts.

Horizontal machining centers: The spindle axis is parallel to the worktable. They usually have an automatically indexing rotary table (fourth axis), allowing machining of multiple surfaces by rotating the workpiece in a single clamping operation. They are ideal for machining box-shaped parts.

Applications of Three-Axis Machining

The applications of three-axis machining cover almost the entire manufacturing industry:

Parts Manufacturing: Producing various mechanical parts, such as brackets, plates, housings, gears, etc.

Mold Industry: Used to manufacture mold cores and templates for injection molds, die-casting molds, and stamping dies.

Aerospace and Automotive: Machining non-core load-bearing structural components, such as brackets, controller housings, and interior parts.

Electronics: Manufacturing equipment housings, heat sinks, fixtures, and jigs.

Prototyping: Rapidly and accurately manufacturing functional prototypes for design verification.

Advantages of Three-Axis Machining

As engineers, we choose three-axis machining primarily based on its irreplaceable advantages:

High Cost-Effectiveness: Lower equipment purchase, maintenance, and programming costs compared to multi-axis machine tools.

Mature Technology and Simple Operation: A very mature technical system; CAM programming is relatively straightforward, requiring less technical expertise from operators.

High Precision and Stability: Due to the relatively simple mechanical structure and easily guaranteed rigidity, extremely high precision and stability can be achieved when machining a single plane.

Quick Programming and Setup: For simple geometries, programming and preparation time is short, making it ideal for small to medium batch production.

Disadvantages of Three-Axis Machining

Understanding its limitations is crucial for making the right technology selection:

Geometric Limitations: The biggest limitation is its inability to machine parts with complex curved surfaces or requiring multi-angle features. For parts with deep cavities, deep holes, or features on the back side, multiple reclamping operations are required.

Multiple Clamping Issues: Reclamping not only increases auxiliary time and reduces efficiency but also introduces repeatability errors, affecting the overall accuracy of the part.

Efficiency Bottleneck: For complex parts, compared to five-axis machining, its material removal rate is lower, and the machining path may not be optimal.

Surface Quality: When machining steep sidewalls, the tip linear velocity of the ball end mill approaches zero, potentially leading to a decrease in surface quality.

Three-Axis vs. Five-Axis Machining

Choosing between three-axis and five-axis machining is a core trade-off faced by engineers.

Five-axis machining adds two rotary axes (such as A and C axes) in addition to the three linear axes X, Y, and Z. This allows the cutting tool to approach the workpiece from any direction.

Key Differences and Choices:

Complexity vs. Simplicity: Five-axis machining is suitable for complex curved surface parts such as impellers, turbines, and precision medical implants; three-axis machining excels at prismatic parts and two-dimensional contour machining.

Single Clamping vs. Multiple Clamping: Five-axis machining allows for "one clamping, five-sided machining," greatly improving the accuracy and efficiency of complex parts; three-axis machining requires multiple clampings to complete multi-sided machining.

Cost vs. Value: Three-axis equipment and programming costs are lower, making it the cost-effective choice for most common applications; five-axis machining requires a higher initial investment but creates higher value when handling specific complex parts.

Engineer's Decision Guide: If more than 90% of the features of your part can be machined from a top-down view, then a three-axis machining center is the most economical and reliable choice. Conversely, if the part involves features from multiple spatial angles, five-axis machining should be considered.

Conclusion

In summary, three-axis machining is not an outdated technology, but rather one of the most robust and efficient fundamental solutions in manufacturing. It strikes a perfect balance between precision, cost, and ease of use. As an engineer, my advice is: fully understand your product design, production volume, and cost budget. For the vast majority of parts with non-extreme structures, three-axis machining remains the optimal and lowest-risk manufacturing strategy. It is the backbone of modern manufacturing systems, while more advanced technologies such as five-axis machining are powerful extensions built upon this foundation to solve specific complex problems.